Lt. Paul C. Grassey, World War II B-24 Combat Pilot, Community Treasure.

Following high school graduation, and awhile later at age 19, Paul Grassey had some important decisions to make. Although attending college was part of the mix, the reality of the times really came down to either enlisting in our military or waiting to be drafted! He spent time talking about options with many of the same buddies he’d spent years playing sports with in high school. He remembers asking the father of one of his good friends what he thought he should do. Turns out this gentleman had actually flown as an American aviator with the legendary French Lafayette Escadrille (1916-1918, prior to America’s entry) during World War I. One weekend later, Paul remembers his friend’s dad coming downstairs wearing his full WW I uniform with Captain’s bars and wings. At which point, he announced to Paul and his amazed, but still undecided whether-or-not-to-join-up, friends: “I’m leaving Tuesday. You guys make up your own minds!” This patriot WW I flyer had actually decided to serve his country, yet again, re-entering the Army as a pilot, and he would fly 9 missions overseas. Best of all, given his remarkable effort, he survived the war. That re-entry action so impressed Paul, that it became his decision-point. Enough wondering. He decided, then, to enlist in the Army Air Force. Said he: “I made that decision because, to me, it was important. The world was on fire. I wanted to do what I could to serve and help my country.”

Paul Grassey in pilot training.

Paul knew he wanted to fly for America in the war. Most of all, he wanted to fly as a pilot. At an earlier time in the war, the requirement for pilot training was a minimum of two years of college. As the war progressed, and U.S. air casualties mounted, the rules changed, the requirements lessened, meaning that he could now be eligible for flight training with just three-months campus time. And that he did, attending Lafayette College, taking some coursework but, importantly, also gaining 10-hours of flight time in a Piper Cub. Requirements met, and with additional initial training completed, it was off to Nashville (TN) for, among other things, placement testing to determine whether young Mr. Grassey would qualify for pilot training or, instead, join the war effort in the air as a navigator or bombardier officer. Paul scored well on the aptitude testing and was officially selected for pilot training. With those sequences successfully completed, in the 1943-44 time-frame, he graduated from flight school, pinned on his wings, and became an Officer in the U.S. Army Air Force.

Paul Grassey (second from left, kneeling) with his B-24 crew before heading to England.

From the air base in Charleston, S.C., then on to Mitchell Field on Long Island (NY) to pick up their newer model, the B-24(M). And from there it was off for Bungay, England (with refueling stops along the way) to join the Eighth Air Force’s 446th Bomb Group and the air war against Nazi Germany, then already long underway. It was December 1944, when Paul and his crew arrived to do their part against a still determined, powerful, and stubborn enemy. Paul Grassey would pilot a total of 13 missions in air combat through the still-hostile, war-torn skies of Europe. Throughout all those missions, miraculously, he doesn’t recall his aircraft ever being hit, by either ground fire or from the guns of a Germany fighter. Clearly, Paul and his crew-mates had an impressive Guardian Angel!

Ironically, the closest he and his crew came to having their aircraft fall out of the sky was over the North Atlantic on their initial flight from America over to England! Despite refueling at the prescribed locations along the overseas route, for some reason, at some point, Paul became aware that they were running low on fuel. They were then seven-hours from re-fueling in Greenland, but the instruments were telling Paul they had only six-hours of fuel left! Needless to say, that math wasn’t working.

Now, ordinarily, the pending problem could be solved fairly easily. The much-improved M-model aircraft they were flying was equipped for the journey with a so-called “Tokyo” tank carrying extra fuel for just such a potential emergency. All that had to be done was for the crew’s Flight Engineer to transfer the needed fuel to the main engine tanks. Basic procedure, one would think, except Lt. Grassey quickly learned there was a bit of a problem, when his Flight Engineer confided to him that he couldn’t make the transfer. When asked why, he stunned his pilot by responding: “Because I don’t know how to do that!” Likely just about the last thing a pilot on the verge of a crisis would ever want to hear. What to do, and do quickly, in this well-before-Google era (!). Well, they got on the aircraft’s radio, indicated their dilemma, and out there, somewhere, another Guardian Angel, this one in uniform, answered. Seems there was a booster pump located behind the cabin door, with a switch on it that had to be set to the ‘on’ position. That life-saving instruction in hand, the fuel transfer was successfully (and thankfully) made.

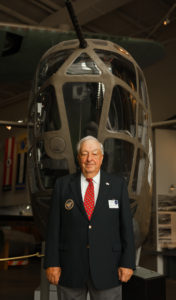

Lt. Paul Grassey, WW II combat pilot.

Worth noting that, at that time, out over the ocean, they were cruising at about 13,000-feet, flying through December winter weather, and as mentioned earlier, they had been several hours away from their next re-fueling stop. Serious stuff. Paul remembers that four other B-24 crews were lost, and never found, making that same North Atlantic transit. Hard to think that the lives of his crew of ten young Americans could very well have been lost to the unforgiving seas of the North Atlantic without ever getting to their base in England, or flying a mission in actual combat, which they had all been trained for, and were anxiously expecting to do.

The other flight that, after some 75-years, remains riveted in Paul Grassey’s mind turned out to be the mission that never was. Had it happened, it would’ve given Paul 14 total missions flown in combat. As it was, it was still very much flying in a combat environment. Following the morning crew briefings, Paul and his crew rode out to their plane, did their internal checks, and prepared for their turn to take off. B-24’s, he said, required more ground speed for lift off than the B-17’s, but, regardless, the runways all seemed to be the same length! Concern was always about clearing the trees which, with American bases in England, inevitably seemed to be always standing there as the runway pavement was coming to an end.

When they left England that day, the weather was clear and fine. Those conditions didn’t last. Once over the continent, and with the remaining two-hour flight to Paris, the conditions had deteriorated severely, with heavy rain and lightening covering the flight path for hundreds of miles forward. As Paul recalls, there were now about 150 American bombers, 17’s and 24’s, circling later over the French capital, trying to both link up with their mission leads, while at the same time trying hard not to collide with any of that large number of aircraft circling and waiting around them in blinding weather.

At some point, the radios came alive with word from headquarters that, due to the weather, their mission(s) for that day had been cancelled. Disappointing for the aviators, hoping they’d have been one mission closer to completing their total and heading back home to America. But yet, a relief not to have to plunge forward through such dangerous flying weather, over territory still very much in enemy hands. The visibility was reduced to the point where even finding, let alone hitting and destroying, their assigned target(s), was in serious doubt.

And then their return flight to England got even more challenging, yet, since their plane’s radar had, for some reason, gone out! Adding to the headaches, the rain water was by then hitting the aircraft so hard, that it was actually leaking through the pilots’ front windshield! So, in the skies over Paris, in the midst of weather chaos, the circling bombers carefully made a sweeping half-circle back around to head, much sooner than anticipated, back “home” to eastern England. Now, absent any allied fighter support, which had also been called back, the bomb group would have to fly over Belgium, and its dreaded port city of Antwerp. Dreaded because it was still very much occupied, and featured a sizeable number of German anti-aircraft guns (“88’s”) protecting this key German-held port. And to make matters even worse, particularly in poor-visibility weather, along with those ever-lethal flak guns, Antwerp was surrounded by a large array of barrage balloons, whose steel cables could bring down a low flying bomber with one strike of a wing. This added threat, while Paul and the others were already flying lower than normal, in order to try to avoid alerting German fighters on the ground, whose radar was quite likely still working!

Paul Grassey in flight.

There were 23 B-24’s flying in Paul’s group. He wasn’t certain, but he remembered that either three or four of them did end up being shot down by German ground fire. Fortunately, for Paul and his crewmates flying this, as it turned-out, non-mission (although very much still in combat), their aircraft did make it safely back to their home field in England. With noted relief and classic understatement, from this and all of his missions facing enemy air and ground fire, as Paul recalled: “Combat is 95% luck. There are just so many ways to get killed!” Fortunately for Paul, his luck in the air never ran out. Thankfully, it won out.

When it came to bomber piloting skills in combat, Paul Grassey was the proudest of his ability to maintain his aircraft in a tight group formation in the air. Tight formation meant flying virtually wing tip to wing tip, with only a few feet separating one B-24 from the one on either side. This was done to provide the most self-protection possible for our bombers from the attacking German fighters, by maximizing the concentration of our aircrafts’ defensive machine gun fire. Tougher for an enemy fighter to pick off one of our bombers flying amidst that barrage of returning fire from our array of gunners (front/back/sides/beneath). Paul indicated that one time (at least), unhappy with the loose formations he saw among his bombers, pilot and leader, General Lew Lyle, actually flew right through the formation to prove his point that his guys weren’t flying nearly close enough for maximum safety! With that dangerous and dynamic example, pretty sure General Lyle made his point!

Asked what sensory memories he recalled the most while flying within America’s bomber armada through those death-dealing enemy skies, Paul remembered, perhaps most, the “awfully noisy” (but yet comforting!) sound of those four powerful Pratt & Whitney engines. Next, was the constant aroma (make that, smell!) of oil coming from those same sturdy and reliable big engines. Then, once in actual combat, along with keeping his head on a swivel to maintain safe distances in formation, while ever-scanning the sky for enemy fighters, he remembers the cascading sound of machine gun shell casings pinging off the steel-plated flight deck, just behind the pilot seats, as the flight engineer manned the defensive forward machine gun over-head.

In addition to having a longer range than their sister B-17’s, the normal cruising speed for a B-24 was also faster. Generally, an advantage, but it did mean that they could not do formation flying with B-17’s. Said Grassey: “If we were to throttle back in order to stay with them, we could end up actually staling-out!” He did feel that the B-17’s were more “air worthy, however, because they had that “big wing.”

Not surprising for any sane person, when asked what scared him the most flying in combat, facing both ground an enemy aircraft fire, Grassey replied without hesitation: “Being shot at!!” And what quickly became quite apparent to him in that situation, he recalled: “They’re actually trying to kill us!” He remembered feeling the most uneasy just as the action from below and above began. “I didn’t worry as much while flying tight formation and the guns were firing. There wasn’t time for worry then. Way too much going on. Were we scared? Of course. But upfront, at least we could see what was going on. The guys in the back of the plane didn’t really know what all was happening. Maybe somehow that was better?” Speaking of the guys in the back, there was one gun position, he was glad wasn’t his. “The guy in the ball turret. I wouldn’t want that job for anything!”

Grassey did recall clearly the impact of those flack shells coming up and bursting around them: “The flack was brutal. Maintaining formation for protection, with that flack exploding all around us, all we could do was sit there, take it, and hopefully keep flying.” With their bomb load finally dropped on target, the immediate requirement was to “re-trim” the now-lighter aircraft in order to regain that tight formation among the other 24’s. Formation “was the best self-protection we had,” remembered Grassey.

In flight, the two pilots would take the controls twenty-minutes on and twenty-minutes off, so that they could each stay alert on those sometimes very long flights, especially as American and British ground forces moved enemy troops and their defenses further and further back into Germany. In that regard, he distinctly recalled one particular mission deep into Germany. This time it was the ultimate Allied objective: Berlin. Grassey mentioned that there were somewhere close to 24,000 defensive anti-aircraft guns ringing that capital city. And here comes another classic Paul Grassey understatement: “The more guns, the more trouble you could get into!” He singled out that Berlin mission for its obvious heavily-defended challenges: “That was a very tough mission. It was just total action.” Sometimes they faced more “action” from the flack guns, while other times it was more from the enemy fighters. While they did have at least some basic pre-mission intelligence presented to them during their preparatory briefings, the reality of what they would face could never be fully known back then just from staring at a very large area wall map! Despite the best possible intelligence and pre-planning, as combat veterans, through the decades know all too well, the harsh reality of combat never fully reveals itself until that first actual contact with the enemy, on the ground, at sea, or in the air.

Thankfully, for Paul and Allied forces throughout Europe, the four-year war there for America’s military (six-years for Britain, France & others) finally ended with Germany’s unconditional surrender on May 7, 1945. From that point, Lt. Grassey and thousands of other American pilots assigned to the European Theater received orders to return to the United States and prepare to join their colleagues in the continuing fight against the remaining Japanese forces still battling in the Pacific. Thanks, ultimately, to the American-developed atomic bomb, and the massive Army Air Force B-29’s capable of transporting and delivering them it on-target, the war with Japan ended, and it did so, without the necessity of Allied forces having to invade the Japanese homeland, saving the lives of countless Americans, other Allied troops, and additional Japanese. Thankfully, then, it was no longer necessary for Paul Grassey to join that fight. He was back on American soil and honorably discharged from the United States Army in November 1945.

Once back home, he enrolled at Lafayette College (Easton, PA) where, in 1948, he completed his war-interrupted B.A. degree. He then went to work for the Burroughs Corporation, a dominant producer and distributor of office equipment, then very much in demand, as the nation’s businesses and industries experienced accelerated peacetime expansion, innovation, and productivity. Paul spent a total of 37-years with Burroughs, moving often, each with increasing responsibilities, finishing his career with the company in New York City as District Sales Manager, by then with about 500 employees under his leadership. He and his wife Nancy (a former Air Force nurse) then moved to Savannah, Georgia as their retirement home in 1988, for which this community has been continually grateful.

Paul Grassey and Scott Loehr (Museum President & CEO) at lunch at the National Museum of the Mighty Eighth Air Force.

Paul Grassey at the Museum.

Paul Grassey became associated with The National Museum of the Mighty Eighth Air Force (the command with whom he flew), as both a tour leader and Board member, during the entire 25-years, to-date, of this outstanding historic Museum’s existence (1996-present). In 2013, Paul authored the book, It’s Character That Counts, in which he described memories from his youth, wartime, and post-war business career, including key friends and mentors who were a positive influence on him, due to favorable, and memorable, aspects of their personalities and positive character.

In January 2020, Paul Grassey received the French Legion of Honor, a medal which since 2004 has been awarded to “American veterans who risked their lives during World War II during one of the four campaigns for the liberation of France.” Coming to the Museum from his headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, Consul General of France, Mr. Vincent Hommeril, made this special presentation in front of a large number of Paul’s family members, friends, and a contingent of service members from the near-by 165th Airlift Wing of the Georgia Air National Guard. All were there to congratulate Paul for this high honor, reflecting a portion of his courageous actions and efforts during World War II.

Remembering Paul Grassey.

In addition to his activities with the Museum, still very active and on-the-go, Paul Grassey is a much-requested public speaker, making frequent presentations to area schools, conferences, and civic groups. Along with speaking, he thoroughly enjoys singing patriotic songs and tunes from the 1940’s, which with his very pleasant baritone voice, the audiences always enjoy hearing. Paul Grassey and his wife Nancy remain long-time honored members of the Savannah community. We laud, honor, and deeply respect the service that both have given to our great nation.

(Interview sessions for this career narrative were conducted during November 2020. At age 97, following a brief illness, Paul Grassey passed away on Sunday, April 11, 2021. Rest well forever, dear friend to so many … a truly devoted, inspirational, and courageous Great American.)