Esteemed Military Pilot and Flight Instructor Extraordinaire: LTC Jack Scoggins, USAF (ret.)

Air Force Lieutenant-Colonel (ret.) Jack Baxter Scoggins, born in 1931, was raised out in a country home, near Logansport, Louisiana, some 30-miles south of Shreveport. So far out into rural Louisiana, in fact, that in order to function, “daylight had to be piped-in to them,” he recalled, which we’ll take on faith was more a slice of sarcasm, than actual reality. Following high school, where he participated in JROTC, Scoggins attended Louisiana Technical University (Ruston, LA), graduating in 1954 with a degree in mechanical engineering, and as an ROTC cadet there, also received a reserve commission as a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force.

His desire was to secure an assignment in the Air Force appropriate to his engineering degree, but slots to his liking were not then available. His only other reasonable choice: pilot training. For the record, unlike oft-heard tales of men and women whose dream was to flying from a young age, that was not the dream or the goal of engineering-oriented, fresh new Lieutenant Scoggins. In fact, at that point in time, he had no thoughts at all of making the Air Force his career. But for the time being, his official orders, desired or not, were to pilot training, a sequence destined to develop within him, not only a military aviation career (a widely varied one, as we’ll see), and a lifetime love of flying.

Scoggins followed the prescribed pilot training sequence back then, first to Columbus Air Force Base (Mississippi), were he learned the basics in Piper Cubs and T-6 trainers. Then onto Reese AFB (Lubbock, TX) to gain proficiency flying T-28’s, and, back then, WW II-vintage B-25’s. Final stop on the training sequence, heading forward, now, as he was, on a multi-engine path, in 1955, Scoggins was sent next to Donaldson AFB (Greenville, SC) to train on the aircraft he would then fly for the next 16-years, the comparatively-massive, certainly back then, C-124.

The C-124A Globemaster II entered Air Force inventory in 1951. It was a four-engine, long-range, heavy-lift, multi-role aircraft, flying with a crew of five (pilot/co-pilot/navigator/two flight engineers/loadmaster). When asked about handling this very large plane, Scoggins only memory of concern was the fact, that on final approach, the huge nose of the aircraft naturally came up, obstructing the vision pilots normally enjoyed in the moments before touch-down! All in all, he recalls that he “loved to fly” the C-124. It was fairly easy to fly, said he, “once you got the hang of it!”

Jack Scoggins literally flew the Globemaster around the globe and back. From flying cargo well into Northern Canada in support of America’s defensive Distant Early Warning (DEW Line) site work, to missions throughout Europe supporting U.S. Air Force bases there, to Antarctica re-supplying scientists working at McMurdo Sound, to flying cargo through the Berlin Corridor, proving to the East Germans our capability and intent to remain steadfast. From time to time during the latter flights, Soviet MiGs would come up to “escort” these transport flights in and out of the corridor, certainly a “nice” gesture, though hardly welcome!

Then, in 1958, Scoggins began a three-year tour at an AF base in Japan. The principal mission was to bring in supplies, and especially fresh vegetables, to American troops stationed in South Korea, as well as transporting our military members to and from R-&-R breaks in Japan. During this time, events in that part of the world were re-igniting. On one such fight, the Scoggins crew was dispatched to Bangkok, Thailand to evacuate U.S. personnel from our embassy in Laos. Also during this period, Scoggins and another pilot were sent on a secretive mission to a Southeast Asia nation, assigned to travel the country looking at aircraft accommodation capacities of the airfields they located there. Important information ahead of the hostilities that would soon begin. It was during this mission-challenging time, stationed in Japan, that Jack Scoggins received his promotion to Captain.

In 1961, he was transferred from that pre-war part of the world to a completely different place and responsibility. For the next three-years, Captain Scoggins would serve on the ROTC instructional staff at Tulane University in New Orleans, preparing cadets for military service and, with the way of the world situation at that time, likely eventual deployment to yet another Far Eastern fight.

Following the ROTC assignment, Captain Scoggins returned to the air, spending two-years (1964-66) flying C-124’s out of Hunter Field in Savannah, Georgia. His supply and support flights were, once again, worldwide, to include South Vietnam. Those round-trips could extend to 3-weeks in duration, transiting from Hunter to California (Travis AFB) to Hawaii to Guam to the Philippines, and on into South Vietnam, then reverse course to home. It was during this stationing that Scoggins was sometimes involved with the transport of nuclear weapons, both as a training officer (the safe handling of such, air & ground), as well as piloting missions for delivery of such anywhere in the world they might be needed. Fortunately, the deployment and actual use of such weaponry apparently never came to pass during the Vietnam conflict.

After his Savannah tour, it was back to Japan at Tachikawa Air Base (west-side of Tokyo), a main cargo and troop carrier hub, for a second stationing there. Along with his flying duties, he also served as the Airlift Command Post Officer-In-Charge, with overall responsibility for transport aircraft loading, unloading, and getting all flights into, and out of the base on-time. In Japan, he was attached to the 22nd Squadron, the last of the active-duty Air Force C-124 squadrons in the United States, as other airlift assets were making their way into America’s transport inventory.

Over a 16-year period, Jack Scoggins had flown about 5,000-hours in that work-horse aircraft, in the latter years, to include supply flights from Japan (Tachikawa) to South Vietnam. On one such landing in DaNang, ,U.S. F-4’s were flying close overhead, bombing enemy troops off the end of that same runway! Making it a much “hotter” and more challenging landing for Scoggins than he and his crew had normally experienced! Sometimes combat did come too close for comfort. After landing at Tachikawa after one mission, the maintenance crew called Scoggins later to let him know they had found two bullet holes in his C-124’s flaps!

After all those years flying the venerable C-124, a decade-and-a-half and 5,000-hours worth, service life for now-Major Scoggins was about to change dramatically. As 1970 approached, he received new orders from the Air Force, sending him back to the states, first to survival school, then to helicopter training, and upon completion, on to stationing near Vietnam! Little about these orders sat well with Scoggins, except possibly the returning to the states part! Regarding the Vietnam-area assignment, he recalls his first reaction was “Like hell you are!” But, as every service members knows, or will remember, orders are orders, and Major Scoggins packed for home.

Unexpectedly in all of this, he would be transitioning from a heavy airlift, multi-engine transport plane, to learning to fly military helicopters. As it turned out, his transition was not at all that unusual at the time. With our involvement in the effort to contain the Communist threat in Vietnam, attempting to protect the southern half of the country especially, the need for helicopter crews had become so great that U.S. pilots were being pulled from all fixed-wing aircraft, not only transport, but from bombers and fighters as well, for cross-training in piloting helicopters, mandated by the intensity of the growing war-time need.

So, Major Scoggins was by no means alone in this war-time-demand transitional phase. His first stop state-side was Fairchild AFB (Spokane, WA) for survival school, a critical step for those who would soon be flying in areas thick with ground fire. The course began with five-days of POW indoctrination, typically followed by a 7-to-10-day stint in the woods learning to survive on the land. As luck would have it, and much to his delight, Scoggins was pulled from the school prior to the woods phase, because his helicopter training class was scheduled to begin. So rather than a week alone in the wilderness, he headed to Shepard AFB (Wichita Falls, TX) for a four-month introduction to the whole new world, for him, of flying military helicopters, beginning with the UH-1 (Huey), followed by the twin engine HH-3 (Jolly Green Giant).

Then it was off to Eglin AFB (Florida’s western panhandle), where he first encountered the much larger, more capable HH-53 (Super Jolly Green Giant).

HH-53

Globalsecurity.org describes the Sikorsky HH-53 as “the first helicopter specifically designed for combat search and rescue operations. It was faster and had nearly triple the take-off weight of the HH-3…larger, more heavily armed…with better overall performance and hover capability, especially at altitude.”

When asked about the difficulty transitioning from fixed-wing to helicopter flying, he recalled that “it was kinda rough.” The hardest thing he remembered having to do, initially, was to work out controlling the landing on a precise spot. “You’ve got to descend and then stop right over that landing spot, and for the first while, I had the darndest time stopping that cotton-picking thing over the spot!” As you might imagine, for a pilot with his experience and determination. it wasn’t long before he was putting those helicopters down, from the beginning Huey to the Super Jolly Green, right where they needed to be. Scoggins recalled that the HH-53 was actually easier to fly than the Huey. Among other reasons, it had a lot more power. “It was a very big helicopter, and I had just come out of a very big airplane, so that’s probably why I liked it so much.” Transitional flying training finished, Jack Scoggins was off to Vietnam.

But before his final destination, there was a five-day stop in the Philippines for jungle survival school. And on this round, it was time to go into the woods (jungle, actually!). The objective was to stay out there overnight without being spotted. Young local men were offered a reward of one-pound of rice for every American they were able to uncover out there in the darkness, a handsome incentive in those days. So off Scoggins went into the jungle, positioning himself back off of a trail, convinced that, by sun-up, he’d remain undetected. He told himself “I’m gonna make it, I’m gonna make it.” The next thing he remembered was feeling a hand on his shoulder belonging to a young Philippine lad, asking Scoggins for the “chit” that would prove he’d earned yet another valued pound of rice. Later, Scoggins asked one of his buddies how they’d found him. As it turned out, no real mystery there. “You fell asleep. You were snoring like hell,” said his buddy! To guard against that give-away in the future, should he need to be in hiding, once arriving in Vietnam, he promptly secured an ample supply of No-Doz tablets!

The year is 1970. Now in the Vietnam combat region, Scoggins was stationed at an American Air Force Base in Udorn, Thailand. It was from that location that he and his unit comrades would fly their combat search and rescue (SAR) missions, the principal purpose and responsibility of the Super Jolly Greens. Eight of the Jolly Greens were situated at four different locations, all on constant alert, with two of them on heightened-alert forward, at a site in Laos. For the latter, on a rotating aircraft basis, two HH-53’s would fly there each morning, land, monitor the radio, and wait for a rescue call. Near dusk, they would then fly as close as possible to that day’s designated “strike zone,” circling at a safe distance, in the event of a pilot down. Receiving no call, with night fully upon them, they would make the return flight to Udorn (there was no nighttime rescue capability at that time). Anytime two crews were scrambled for a rescue, two additional Jollys would fly to their alert location to cover for them.

A C-130 (“King Bird”) was always airborne at altitude for each rescue mission, serving as the on-scene operations supervisor and communicator, both with those involved with the rescue effort and with our military authorities in Saigon (all rescue launches had to be authorized by Saigon).

Along with the on-scene supervising aircraft, a second C-130, serving as a tanker,

HH-53 Air Refueling with C-130

also launched on every mission, ready to refuel the Super Jolly Greens, when needed, especially critical after an extended time-on-station, first while searching (and/or dropping fresh batteries to the downed pilot to maintain radio contact, if he was attempting to move to a safer location), and then during the hopefully rapid actual pilot rescue, the fresh fuel allowing for a safe flight back to the designated base. And speaking of the need to refuel in-flight, Jack Scoggins memory is crystal clear on his longest flight: 8-hours & 15-minutes, all without leaving the pilot’s seat!

Scoggins had originally been assigned to DaNang, but at that point in the war, there were no HH-53’s at the facility in DaNang. The Super Jolly Greens, the helicopter he was trained and assigned to fly, were, however, at Udorn. And there’s an important side-note here. Jack Scoggins wife, an Air Force nurse, was currently assigned to Udorn. Scoggins got on the phone, and as luck would have it, the person he reached in personnel was an old friend. Scoggins explained about the availability of HH-53’s, but not at DaNang, and, oh by the way, mentioned that his wife was already stationed at Udorn. The friend in personnel promised to look into his transfer request. Two weeks later, he got his revised orders to Udorn, Thailand! Sometimes things do work out right!

Major Scoggins (on the left) with his HH-53 crew.

Jack Scoggins would fly virtually all of his missions out of the U.S. base at Udorn. A few of those missions and experiences remain vivid in his memory. One such was the assignment to take three crews and two HH-53 aircraft to set up a small flight facility inside South Vietnam. Scoggins was the ranking officer with responsibility for getting this small, satellite airfield up and running with communications, crew quarters, etc. At one point during that process, the call came to scramble for a rescue. Typically two aircraft would respond, one flying up above the other (“high bird”), for back-up, while the other (“low bird”) searched the ground for our downed pilot.

Since Scoggins, as senior officer, was then elbows deep in the logistics of the operation, he turned his helicopter over to another pilot, and the two aircraft then lifted off to commence the search. Before long, word was radioed back that the “low bird,” the aircraft Scoggins would have been flying, had been shot down, with all five lives aboard lost (pilot/co-pilot/engineer/two para-rescuers (“PJ’s”). Sadly, Scoggins called back to his squadron commander at Udorn to report the tragic loss. He remembered being startled at first by his commander’s initial response over the radio, when he said immediately: “Oh, thank goodness, Jack. Thank goodness it wasn’t you!” The reason for his relief to learn that Scoggins had not been killed on that flight, in the very aircraft he would normally have flown, was not out of any lack of remorse for the loss of his squadron crew members, but rather, as Scoggins recalled, because his commander had dreaded the thought of having to go over to the base hospital at Udorn to break the news to Jack’s wife face to face! Five courageous men had taken Jack Scoggins aircraft and mission response that day. A mission he normally would have flown. That fact, and the resulting loss of his comrades, still weighs heavily on him.

While finding and rescuing downed American pilots was the primary mission, occasionally there would be others. One such involved extracting several Laotian soldiers, in danger of being overrun by Communist forces, along with family members (and sometimes even family animals, the so-called “people and pigs” rescues!!) from a small airfield in Laos. This involved pulling a few of them on-board, then hovering to see how the helicopter was handling the weight. Then repeat until they had reached maximum weight under maximum power. In that particular instance, at the end of the runway, there was a big drop-off. So, recalled Scoggins: “We would begin our take off, then drop down into that valley, get our flying speed up, and fly out of there.” He remembered that they had undertaken a couple of missions like that, but pilot recovery remained the number one priority.

A typical day for Scoggins, his crew, and others, would be flying from Udorn up to an allied airfield in Laos (or other airfields in the region) and spend the day standing alert, awaiting the call for a rescue flight. One of those subsequent rescue calls should never have occurred. It resulted from an inappropriate action (perhaps the kindest way to express it) on the part of an F-4 Phantom pilot. F-4’s fly with two officers, a pilot and a rear-seater, known in the F-4 as the RIO (Radar Intercept Officer). This particular pilot, experienced and, thus, should have known better, was flying that day with a brand new RIO. The flight was over an active enemy combat area. And it was at night. As it was related to Scoggins from a post-rescue debrief, while in flight, the pilot asked the new RIO “if he’d ever seen ground fire.” The RIO answered “No.” To which the pilot replied “well, I’ll show it to you!”

The F-4 was on a reconnaissance mission at the time. He had flown across a “hot” valley to help determine where the enemy troops might be concentrated. To “show” his new RIO enemy fire, the proved-to-be-foolish pilot then pulled up, “does sort of a tear-drop maneuver, and flies back down low, right back into that same valley, and gets shot down,” related Scoggins. The two crew members ejected and parachuted to the ground.

“What hurt the most,” recalled Scoggins, “was the next day, when we were there trying to get the two crew members out, we heard over the radio that the RIO had been found, shot and killed on the ground by the enemy.” Scoggins learned that the pilot was alive and had made it to a cave. “We worked that mission for three days,” he recalled. “He’s in this cave, he says his back is hurt, and his radio is giving out as the batteries wore down. So we go in and drop batteries to him.” The downed pilot was able to safely retrieve the new batteries and radio contact was re-established.

On the second day, said Scoggins, “every time we’d send someone in to pick him up, the rescue helicopter was shot at and had ended up full of bullet holes. So the aircraft would have to pull off.” Finally, F-4’s and A-1 Skyraiders (“Sandys”) were sent in to strafe and bomb the enemy combatants to try to free up the area for the rescue. And then, said Scoggins, “the HH-53’s would try to go in again, and, again, they’d get clobbered, and would have to pull out.” Clearly, the enemy had figured out that as soon as the F-4’s and the “Sandys” stopped attacking, the rescue would be attempted, and so the ground fire would re-commence whenever the rescue helicopter re-appeared.

So the third day, the rescue team decided to try a different tactic. The pilot was hiding in a cave on the other side of a mountain, somewhat removed from the enemy fire. “So we kept the F-4’s and the “Sandys” bombing and strafing the entrenched enemy in the same location as before, while bringing the HH-53 in from a different direction.” The “low bird” was able to safely low-hover now, and they lowered the “penetrator” with a para-rescueman to pick up the “injured” pilot. At that point, recalls Scoggins, “the pilot came out of that cave like he was doing the 100-year dash. Clearly, there was nothing wrong with his back!”

Nine helicopters had taken part in this rescue effort, and six of them were shot up so badly they struggled back to home station, but couldn’t fly again until extensive repairs were made. “One came back and the landing gear was just dangling,” he remembered, “so we ran to the barracks and got mattresses and laid them down on the runway, so the pilot could land on a pile of mattresses, without having the rotor come down and hit the concrete. That helicopter was leaking fuel and was full of bullet holes, but the crew was down safely. When it was all over, that common-sense-impaired pilot finally rescued, at tremendous expense to aircraft and great risk to crews (two members among the rescue crews did receive bullet wounds), Scoggins summed it up by simply saying: “He caused us a lot of trouble!!” Spoken with the composure of an experienced pilot, that is the understatement of the decade. And as Scoggins recalls, it wasn’t long after, that some of the impacted Super Jolly Green pilots had, shall we say, an intense encounter with that particular F-4 pilot, making their point regarding his errant judgment one to be remembered!

The A-1 Skyraider, known to the rescue community as “Sandys,” was a single-propeller- powered attack aircraft flown in Vietnam by both the U.S. Air Force and Navy. Key attributes were its favorable loiter time, and its ability to carry considerable weaponry (four 20-mm cannons, plus several hard points for rockets, bombs, etc.). The “Sandys” worked in close coordination with the Super Jolly Greens to suppress ground fire so that downed airmen rescues could hopefully be safely made. As with all combat aircraft in a war zone, it was dangerous work, requiring perhaps even more daring, due to the necessity of the Sandys flying down so low over enemy positions to be effective in ground fire suppression. According to Wikipedia, “The USAF lost 201 Skyraiders to all causes in Southeast Asia.”

That by way of background for Scoggins other successful rescue effort resulted, this time, from pilot bravery, as was normal, not foolishness. Scoggins was flying his Super Jolly Green on a mission to retrieve a downed airman. As was most often the case, two HH-53’s were assigned to this SAR call. On this day, Scoggins was flying the “high-bird,” position, while the other was in the “low-bird” slot, with primary responsibility for locating and picking up the downed U.S. survivor. The “high-bird’s” role is to observe, and it anything happens to the primary rescue Jolly Green, the high one’s task is to come in to rescue that crew. With F-4s scanning and protecting the skies from up above, as usual it was the ever-present companions and guardians of the Jolly Greens, the “Sandys,” that were flying in low, strafing any intruding enemy forces, doing all in their heavily-armed power to clear the area for the pilot rescue. Watching the low-level ground-clearing work of these daring pilots, he recalled then witnessing the lead “Sandy” get hit by enemy fire. “He was hit badly,” said Scoggins, “I mean, he was on fire!”

That “Sandy” pilot then pulled up into the air not far from where Scoggins, in his “high-bird” position was orbiting and observing. “So, we got in behind him and radioed: “Sandy-1, this is Jolly 87…. Punch out, we’ll get you.” Scoggins was very familiar with the area, as they had been working it for two days. “It was a hot area, real hot,” he recalled. But rather than follow Scoggins advice to bail out, the “Sandy” pilot just pulled out and kept on flying, no doubt hoping to make it back to a friendly airfield. “By this time, the flames were past his cockpit,” remembered Scoggins who flew to keep up with him. So he repeated his instruction to the pilot: “Sandy-1, this is Jolly 87, right behind you. The flames are past your cockpit!” The pilot responded “Roger that,” and just kept on going. He wanted to get as far away as possible from that “hot” combat area.

“Well, by this time, the flames tore back behind his tail,” said Scoggins. “We moved over to the side and did not get behind him anymore, because we didn’t know whether he was going to blow up!” Scoggins radioed the pilot his flames observation again, assured him they’d rescue him, and once more told him to “punch out, punch out.” Finally, at that point, the wingman of the endangered “Sandy” pilot, flying nearby with him, yelled into the radio: “Oh, damnit it, Tim, get out !!!”

And with that from his nearby wingman, the “Sandy”pilot finally ejected. Scoggins watched as the pilot seat separated and the parachute came out, as the pilot headed for the ground. Complicating Scoggins’ immediate rescue response was the fact that, after flying in that area for some time, previous to the “Sandy” being hit, they had just air-refueled. “So, we were loaded, making us high and hot, so we could not hover with the load that we had. So we had to blow the auxiliary tanks to dump fuel.”

Now, in addition to safely ejecting from an aircraft engulfed in flames, that “Sandy” pilot, with a simple round parachute, no guidance capability, had somehow managed to drift down and land on the top of a mountain in a cleared area! Having successfully dumped sufficient fuel, Scoggins’ Jolly Green was then able to come to a hover just about the time the “Sandy” pilot hit the ground. The crew lowered the penetrator near the incredibly fortunate pilot, and pulled him up to safety. “I don’t think he was on the ground for even a minute,” recalled Scoggins. Once on board, in response to questions about his condition, the pilot indicated he was fine, but hoped he hadn’t scared the crew by shooting his gun on the way up into the helicopter. When asked if he was responding to ground fire, he told them, no, he just “wanted to shoot his pistol.” Coming as close as he did to perishing in an aircraft likely about to explode, and then somehow landing in a perfect spot for a safe extraction, perhaps that pilot can be excused for firing off some adrenalin. Pilot retrieved, with fuel an issue, having dumped a share of it to allow for the pick-up hover, Scoggins then headed for the nearest allied airfield, which was DaNang in South Vietnam.

And one important footnote. The original downed pilot, the reason for that particular mission to begin with, was, in fact, rescued. The remaining “Sandys” successfully cleared the area of enemy fire, so that the “low-bird” Jolly Green could hover and make that survivor pick-up. A successful ending for two downed pilots, and their rescue crews, all the way around.

But there is an unusual, if not truly amazing coincidental, twist to this “Sandy” rescue story that occurred some thirty-years later. Then retired from the Air Force, Jack Scoggins had become a highly-regarded commercial pilot and the owner of a flight school at the airport in Valdosta, Georgia (his wife, then still serving as a senior nurse officer, was assigned to Moody Air Force Base outside Valdosta). As a designated pilot examiner, Jack was required to take a flight-check every year from an FAA inspector to renew his certification. On this day, he had to fly up to Knoxville, Tennessee to take his annual glider flight-check from an inspector at the District Office there since, at the time, no one in the Atlanta office was qualified for glider certification testing.

Previous to his arrival in Knoxville, the FCC inspector had advised Jack that he had three exams to give, but there was only time for two. He told Jack that he’d give him his exam first, and then asked if Jack would, in turn, administer the test to the remaining candidate so that he, too, could obtain the commercial glider add-on to his commercial flight certificate.

Jack was happy to oblige and the flight-check for that particular candidate was successfully administered and completed. Following the exam, while he was finishing up the paperwork, the candidate happened to notice a Jolly Green patch on Jack’s flight jacket. That triggered a conversation: Had each served in Vietnam, when were they there, etc. Come to find out they had been in the same vicinity at about the same time (1970), and the gentleman he had just glider-certified indicated in their conversation that he had actually been a “Sandy” pilot there. Letting him know that he had, of course, flown the HH-53 in combat SAR missions, Jack said: “We probably flew missions together and didn’t even know it!”

With the “Sandy” connection established, Jack began to relate the saga, detailed above, of that determined “Sandy” pilot, his plane on fire, the eventual bailout, and his safe rescue by Jack and his crew. Jack then added the footnote about the pilot shooting his pistol on the way up the penetrator, just for the sake of doing it. To which the gentleman replied: “Sounds just like, Tim.” So Jack asked if he had actually known that pilot. Without hesitating, the gentleman replied: “Who in the hell do you think was his wingman that day!” Incredible. After all those years, Jack had just successfully flight-checked, and engaged in conversation about their 1970 Vietnam service, with the actual wingman who had demanded that his “Sandy” squadron-mate eject, certainly helping to save his life. The adage “small world” doesn’t even come close to an unbelievable coincidence like that.

Returning in time, now, back to 1970, at Scoggins’ home station at Udorn, Thailand. As he vividly remembered: “One day, we go to our intelligence briefing, and I see nothing but red spots all over the briefing map… heavy gun emplacements, and SAM sites all over the place.” Their tasking that day was to fly up to the western part of Laos, a frequent staging area to await rescue calls, a location known to the pilots as the ‘Fish’s Mouth’, located west of Hanoi, North Vietnam, explaining the heavy defensive concentration ringing the area. Typically, they would fly to a holding area like that, then at about two-hours before dark, they would fly in even closer to the active air-combat area, so that, in the event of a rescue call, they could hopefully get it completed before total darkness overtook the area. As Scoggins mentally processed the intelligence briefing that particular morning, and what he and his crew would no doubt be facing that day in the air, with the continuing likelihood he’d be called in to make a rescue, he remembered saying to himself: “Well, Jack, today, you’re not coming back.” Facing the prospect of bad outcomes, that extreme apprehension in the face of dire circumstances for the Jolly Greens, would later be replaced by miraculous news. The Jollys were on-station, flying apart from the target area, but in the vicinity, there, as always, in the event of an aircraft shoot-down and the need for a survivor rescue.

Scoggins recalled that, on that day, for that operation, we sent up over 100 U.S. bomber and attack aircraft, in a collective attempt to blanket-neutralize that extremely “hot,” heavily defended enemy zone. And it worked, and safely, beyond all expectation and belief. That heavily-armed armada of U.S. aircraft succeeded in taking out all of the enemy’s missile and anti-aircraft sites in and around that particular target area! Even more amazing, it was done with no American casualties. “Not one was shot down!” he remembered, with still to this day, a combined sense of relief, amazement, and awe, realizing the negatives for our pilots that might have been.

The scheduling of “high-bird” and “low-bird” assignments was done as equally as possible, within the reality of combat demands and conditions. By trying to balance the high and low positions, each of the Jolly Green pilots and crews faced the same level and frequency of exposure, especially, of course, for the “low-bird,” which was the primary rescuer (and potential enemy target), unless it was hit, in which case the “high-bird” would drop down into the fight to take on, at that point, perhaps multiple rescues.

In everyday life, clear and accurate communication is important. In combat, its crucial, often making the difference between survival and sacrifice. Scoggins learned of one such case, sadly the latter, involving the loss of a Jolly Green, prior to his arrival in theater. When the high and low Jolly Greens fly to, and determine, the rescue location, two sister aircraft elements accompany them to assist. The “Sandys” go in on low bombing and strafing runs to neutralize the site prior to the rescue attempt, while, secondly, high above, F-4’s fly what is called the “MiG-Cap,” patrolling the skies above the downed-pilot area to keep it clear of any enemy MiG or other airborne interference. On that particular day, the Jollys radioed to double-check that they did, in fact, have top-cover U.S. fighter protection in place (i.e., the MiG-Cap). The reply came back in the affirmative. Whether misinformation or misunderstanding, the reality was there was no MiG-Cap in place, at the time, during that ground rescue operation. Unbeknownst, then to the vulnerable “low-bird” Jolly Green, flying above it and unopposed, an enemy MiG fighter in the area spotted the “low bird” and shot it out of the sky, killing all crew members onboard. An unnecessary tragedy caused by a communication error, during the “fog of war.” The assumption would be that other protective aircraft were rapidly dispatched to that rescue site, and the original downed-pilot retrieved, but that eventuality eluded Scoggins’ memory, at the time we spoke.

He does clearly remember a non-flying tragedy at the Udorn, Thailand air base, which turned out to be a very close call for him, personally. Out on a mission, a USAF F-4 had been shot up badly, and was struggling to make it back to the base. Due to the damage sustained by the aircraft, on final approach, its hydraulics failed. The pilot and co-pilot were able to bail out and survive. But, sadly, the F-4 then crashed into the base Armed Forces Television Network building, killing everyone inside. The resulting fire also destroyed two nearby BOQ’s, though fortunately, all personnel there were able to get out without further injury or fatality. The reason this event remained so vivid in Jack Scoggins mind is that he had been in that very AFTN building just about 5-minutes before the crash! An extremely close call on the ground, let alone his ever-dangerous missions in the air.

During his Vietnam tour, Jack Scoggins would fly over 50 actual combat SAR missions, to include the rescue of two downed pilots, both of which efforts, in addition to saving their lives, earned Scoggins the Distinguished Flying Cross (two DFC awards overall). But despite the acclaim represented by these and other service awards Jack Scoggins received, he was always quick to remind that all missions flown were true team efforts.

At the conclusion of his one-year duty assignment to Thailand (Vietnam), Scoggins returned stateside to Forbes Air Force Base (Topeka, KS) were he was assigned to fly H-3 helicopters with the National Geodetic Survey, as the Wing’s Maintenance Quality Control Officer. As the name indicates, under direction and guidance from NOAA, his wing’s mission was all manner of survey work, primarily, of course, aeronautical. He recalls not being there very long, because, several months after his arrival, they closed the base. Scoggins maintains the closure was in no part due to his performance or presence!

Then, in 1972, the Air Force sent Major Scoggins to Patrick Air Force Base (Satellite Beach, FL). After completing the required water survival training course, he was back flying the HH-53 helicopter, this time preparing for the possible need for space capsule recovery in the ocean (both shallow and deep-water), or on land, should a problem occur for the astronauts at, or near, the launch site.

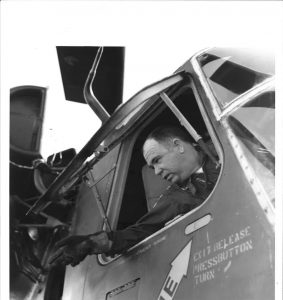

LTC Jack Scoggins at Patrick Air Force Base, Florida, preparing for a possible astronaut recovery flight.

“At each launch pad, they had 120-degrees around it, where there were landing spots,“ he related. “If a fire broke out or if they had to abort and get out of the capsule real quick, they would grab onto a roller attachment and slide down an escape cable to the ground, and we’d be sitting down there waiting for them. Depending on the problem, it would dictate which landing site we’d use.” That was one scenario, he remembered. The other would trigger, just before launch, or immediately after it. Said Scoggins: “If they didn’t have a chance to get out of the capsule and onto that escape cable, they would fire a rocket on the capsule. That would take them up into the air, a parachute would come open, and then they would land either on the land or in the water. We were trained for three different recoveries: land, shallow water, and deep water.” As Scoggins recalled: “About four-minutes after launch, they were out of our range. At that point, our job was done.” If the astronauts had to land farther out in the ocean, that became the responsibility of another recovery team. Scoggins expressed understandable relief that, on his watch, he and his crew did not have to make any rescues. Good news for him. Great news for the participating astronauts! Turns out, there was some great news for Major Scoggins, as well. While he was on the Air Force assignment with the NASA astronaut rescue mission, he received his promotion to Lieutenant-Colonel.

In 1974, after 21-years of distinguished military service, distinguished literally with the awarding of two DFC’s for his combat rescues, LTC Jack Scoggins decided to retire from the United States Air Force. When his officer-wife’s AF nursing assignment took them to Moody Air Force Base in Valdosta, Georgia, they decided to establish their residence there in his military retirement.

But it didn’t take Jack long to visit, and become a fixture at, the Valdosta Airport! Having obtained his flight instructor certification in New Orleans, back during his ROTC teaching assignment at Tulane, Jack took over instructing duties there from a departing teacher, working first for Holland Flying Service at the airport, before joining with two partners to form Air Valdosta, a flight training firm he managed, while also continuing to instruct students. After three-years, Jack returned to flight instruction on his own, as well as piloting corporate aircraft for Valdosta area companies. In addition to basic flight instruction, since 1977, he had also been an FAA-Designated Pilot Examiner, the person qualified to administer flight-checks and oral exams to students prepared for, and seeking, final flight licensing approval.

Jack would spend 40-years, post-military, primarily as a fight instructor, but also taking on pilot examiner duties, as needed. He estimates that, over those years, he has taught over 150 students to fly and prepared them for their licensing (with final tests administered, of course, by another examiner!). Of special significance for Jack is that, having taught his son, Greg, to fly many years earlier, in 2016, one of the final select students that he chose to instruct, and prepare for licensing, was his grandson, 17-year-old Mason Scoggins! Mason, a high school student, residing with his parents in Davidson, NC, spent many summer vacation weeks with his Granddad in Valdosta in order to fulfill the dream of flight held by both. And another crowning achievement came, this one, a year earlier, when veteran teacher Jack Scoggins was named the 2015 Georgia Flight Instructor of the Year, during a formal evening Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame ceremony at the Museum of Aviation, Warner-Robbins, Georgia.

Now, at the age of 85, Jack continues to both instruct, and to pilot his own aircraft. Lieutenant-Colonel (ret.) Jack Scoggins, a distinguished military veteran, and a life-long genuine American patriot.

William L. (Bill) Cathcart, Ph.D.

Copyright: December, 2016