Help From Above, Whenever The Need: Always Ready! United States Coast Guard Captain J. Marshall Branch, Rescue Helicopter Pilot

Young Marshal Branch with his Dad, while living and serving with the U.S. Army in Germany

Marshall Branch knew from an early age that he wanted to fly, and, most importantly, he wanted to do so in America’s military. Military was always an important part of his family growing up, from his grandfather serving in World War II, flying with the Mighty Eighth Air Force, to his father who served as an Army officer during Vietnam. And it was his Dad who “instilled an incredible sense of civic responsibility in our family. We just grew up in a family of service,” recalled Branch. For him, flying as a career was never a question of if, but always a matter of when, where, and for which of the services. Early on, he had, perhaps naturally, gravitated toward the Air Force, since his dream then was to fly fighter aircraft. “The movie ‘Top Gun’ had come out around that time, and of course every teenage boy then wanted to be a fighter pilot,” he said.

Then fate intervened, as it often does, this time in a very positive way for his future. With the family now living for a couple of years in New Jersey, like his Dad’s earlier achievement, now an Eagle Scout in the making, Branch’s Boy Scout troop had a trip planned to Mystic Sea Port in Connecticut. Following that experience, on the drive back to New Jersey, they noticed an exit sign for the United States Coast Guard Academy. Not on a tight return schedule, his Dad decided to take the troop over for a look. They toured the campus, and on that day, a Coast Guard Cutter was tied up at the pier, giving them an opportunity to talk with the crew. “I started to realize that there was a lot about the Coast Guard that I really liked, with missions such as law enforcement and search & rescue. That visit put the Coast Guard on the radar for me, and certainly the Academy as an option,” recalled Branch. Then just a seventh grader, his Dad reminds him that, while departing that day through the Academy gate, he turned to him and said: ”Well, Dad, that’s where I’m going to go to college!”

Already exhibiting a serious commitment to public service, with his work as a volunteer firefighter while still in high school, during his senior year, as predicted five-years earlier, Branch applied to the Coast Guard Academy and was accepted. That alone was a distinction. Each year, roughly 10,000 young men and women apply for admission, with acceptance based on key criteria like academics, athletics, civic responsibility, and leadership, all areas in which he had excelled. From among those ten-thousand applicants, only about 300 are invited to enter. Based on his accomplishments, in the obviously very competitive selection, Branch gained admission to the Academy’s Class of 1991.

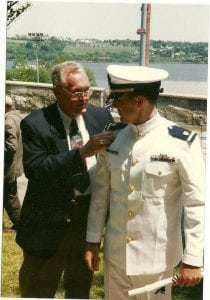

Marshall Branch’s Grandfather, Army 1LT Sam Marshall (WW II B-17 Bomber/Navigator, Mighty 8th Air Force) pins on a shoulder board (Branch’s Dad pinned on the other), at Marshall Branch’s Academy Graduation (1995).

His fondest Academy memories centered on summer training assignments out with the fleet, out with actual Coast Guard units. Those experiences included service on the USCG patrol boat that, as the maritime security command post, was tasked with watching over President George H.W. Bush wherever he went, while vacationing in Kennebunkport, Maine. The time spent with a Tactical Law Enforcement Team (TACLET) in Miami, chasing drug runners in cigarette boats. And part of a summer spent on the Coast Guard Cutter VIGILANT out of Cape Canaveral, FL, and the remainder with H-65 crews at Air Station New Orleans, the latter a welcome preview of his career to come. After four years of study and hard work, Marshall Branch graduated from the Academy in 1995 with a Bachelor’s Degree in Management and a commission as an Ensign in the United States Coast Guard.

As with all Academy graduates, his first tour was two-years at sea aboard the Coast Guard Cutter DAUNTLESS. Among their many sea-borne missions, for decades, now, and still to this day, the Coast Guard has been heavily involved with drug and migrant interdiction efforts. Lieutenant Branch recalled one operation in particular, from those very early days in his career. This was a migrant interdiction.

“You have two different types that you have to worry about on migrant boats. You have the desperate people who gave up everything they had to buy passage on that vessel. They’ve got nothing to go back to. And then you have the ‘coyotes.’ They are the enforcers. They get paid to not let people jump ship. They’ll threaten the migrants in all kinds of ways, even pour gasoline on them! The only time I ever drew my weapon, as a ship board law enforcement officer, was during migrant interdictions off the north coast of Haiti, during my very first Coast Guard tour.”

“I was in one of our small boats,” continued Branch. “We’d have two Coast Guard small boats on either side of the migrant vessel. We’d bring one in, making a lot of noise, and the ‘coyotes’ would come over swinging their machetes. Meanwhile, our other boat would sneak up on the back side and pull migrants into the boat to get them to safety. And then we’d switch sides. We’d have the ‘coyotes’ running back and forth constantly. Well, this one ‘coyote’ figured he would hide within the migrants, and when I pulled the boat in, I was reaching for one of the migrants, a young girl, and the ‘coyote’ popped up with his machete and was about to swing it down on that young girl. I immediately drew my sidearm. Fortunately, he backed down.”

“That group, and others we encountered, had killed migrants before. Anyone disobedient or who made the ‘coyotes’ mad, they would just throw them overboard. There were always sharks that followed migrant vessels! So, then, particularly during the mid-1990’s, it was bad. It was very dangerous out there.”

Branch remembered that the largest single interdiction in Coast Guard history, and that record still stands, was an 80-foot vessel with about 500 migrants onboard. Said Branch: “They were packed in so tightly, that the ones who died just stayed there in their spot because no one could move. We didn’t know how many dead people were on board until we got the rest of them off. It was definitely a desperate time, so we tried to get to those vessels as quickly as possible, because migrant safety was definitely at risk. There were a lot of boats that did not make it,” he recalled.

Jumping well ahead in his career, for a moment, since we’re on the subject of interdiction missions, Branch was involved in counter-drug efforts as well, both on the water and flying, as he explains.

“I remember chasing after them (drug boats) in flight, back in the days before we had armed helicopters. Now, the Coast Guard has an armed helicopter squadron in Jacksonville. They’ll put a 50-caliber round through the engine block of a drug-runner’s boat. That stops them! Prior to that capability, we would just basically ‘squat’ on them and use our rotor wash to try to disrupt their ability to maneuver, giving our boats enough time to catch up,” recalled Branch.

But what if someone on those fast drug boats you were flying down close to was armed? “Back then, there was a gentlemen’s agreement, as strange as that may sound. If all they’re doing was evading law enforcement, they’ll be arrested, but more than likely, they’d be home before our boats got back to home station! However, if you fire on a federal law enforcement officer, you’re not going home, but going, instead, to the penitentiary for a great many years,” he said. “Fortunately, I never had a shot fired at me from a narcotics runner,” said a still understandably relieved Branch.

Back, now, to the proper chronology in Lieutenant Branch’s career development sequence. Following his sea duty, in line with his long-held dream, he was off to fight training at Naval Air Station Pensacola (FL), where he learned to first fly fixed wing aircraft, followed by rotary wing training, and was awarded his aviator wings in 1998.

Following flight school, Lieutenant (jg) Branch was assigned to Air Station Port Angeles, Washington, where he flew the H-65 helicopter and, by merit, gained the designation as an Aircraft Commander. Those stationed there refer to the area as “Alaska Lite,” due to the similarities with Alaska weather and terrain, except they were close to Seattle and “civilization!”

His first rescue flight occurred at Port Angeles. Not long out of flight school, Branch was the co-pilot on what was to be just a training flight, during which he would take the pilot’s seat for practice. Once in the air, they got a call from base that a man, woman and baby in a small boat had run aground after hitting some rocks, a jolt that propelled the child out of its carrier seat, with resulting concern about a possible head injury.

So the radioed instruction was for the aircraft to hoist the mother and child off the boat and transport them to a hospital in Seattle. “I had never hoisted a live person before, in fact I had just become qualified to be in the right seat (pilot), so I was very nervous that my very first human hoist was to be a baby with a possible head injury,“ said Branch. The aircraft command pilot, now in the co-pilot seat, asked Lieutenant Branch if he was OK piloting for the hoist. “I told him, yes, although my heart was pounding about a thousand miles an hour! But the training kicked in, we got over-head above the boat, and I remember looking down and seeing the look in the Mom’s eyes, and thinking, yeah, we’ve got to do this,” he still remembered vividly, now almost two-decades later.

His crewmates skillfully hoisted the Mother and baby up into their helicopter. Branch recalled that “the experience of looking over my shoulder as the basket comes into the door, seeing the survivor(s) in the basket, and you see that look of relief, just sheer relief that things are going to be OK. That hooked me for life. That feeling of knowing that you made a huge difference in somebody’s life, just guaranteed that I’ll be doing this for as long as they’ll let me.”

It was an amazing day in the operational life of this still relatively new Coast Guard pilot. And the great news later to punctuate Lieutenant Branch’s first rescue? After flying them to a Seattle hospital, they learned that the baby had survived the head injuries! They learned that, since the nurses meeting the helicopter on the ground had realized how concerned Branch’s crew was about the baby, they made sure word got to them. The father remained with the boat and was towed in to shore safely.

On Lieutenant Branch’s first duty night at Port Angeles, now as an Aircraft Commander, and the officer in charge, the Navy called with a rescue case, but would indicate nothing more than that the helicopter needed to be at a specific latitude and longitude at a specific time (sunrise), about 30-miles out in the open-water of the Pacific Ocean. “We launched before dawn, arrived at the latitude and longitude, and literally, the moment the clock ticked to the specified time, the USS OHIO surfaced right below us!” remembered Branch. His memory still vivid with the image of that huge American ballistic missile submarine, with its massive steel hull, that had so suddenly fully revealed itself beneath him.

McMurdo Sound in Antarctica. Lieutenant Branch visits with “friends” near the icebreaker, Coast Guard Cutter POLAR SEA (2002).

From radio communication with the sub, as Branch maneuvered into position for a hoist, he learned that one of the boat’s crew had fallen down two levels of steel ladders within, hitting his head on the first landing and and kept tumbling down the second. Once he was brought up top and was positioned for the lift, and the rescue basket was lowered down, “we immediately hoisted the badly injued sailor, and literally, as the basket left the sub’s deck, they were already breaking things down, and by the time we got the sailor to our door, they had the hatch closed and were already starting to go below the surface again,” recalled Branch. That sailor was then flown to Madigan Army Hospital on shore, with no subsequent report on his eventual outcome.

Then, in 2002, came a totally different experience and climate(!) when he was transferred to the Polar Operations Division at Aviation Training Center Mobile (AL) for a one-year deployment with his aircraft and crew abroad the USCGC POLAR SEA for a tour in Antarctica. There, at McMurdo Station, Lieutenant Branch and crew were positioned on land while their host ship went about the necessary work of cutting through the continuingly-forming ice accumulation in order to keep a channel open so that supply vessels could always reach McMurdo.

Cape Crozier on Ross Island, Antarctica. Lieutenant Branch & crew flew scientists out there to study the Adelie penguin colonies. Spent the day helping out, before flying the team back to McMurdo Station (2002).

While on watch there, Lieutenant Branch received a radio call indicated that a contract firm’s civilian helicopter had gone down, some 50-miles distant from their McMurdo location, across the Ross Sea. With 24-hours of daylight in Antarctica, regardless of back-home time, this would be a “daylight” rescue launch, and one into less than ideal flying conditions, punctuated by heavy fog, some wind, and light snow falling. By policy, civilian contractor aircraft were not permitted to fly in the weather conditions that Branch and his crew would face, making the Coast Guard, then, the only rescue source.

For navigation, in an era back before today’s satellite-assisted technology, they had to rely on the old stand-by, charts, because compasses don’t work all that well (“the variance is 178-degrees up,” recalled Branch). “The majority of the navigation in Antarctica is visual, with chart back-up,” he said, making a mandatory rescue flight such as that one inherently risky. Apart from weather conditions, here’s why: “The most challenging thing about flying in Antarctica is that the ice forms just a flat, white layer beneath you when it meets the shoreline, and then blends seamlessly into the glacier, creating what appears to be a continual white slope, so there’s not much contrast or relief, and when your visuals are limited by weather, it makes it extremely hard to navigate safely.” That continual slope-appearing ice can also distort the old-style altimeter readings, because their radar beam can actually pass right through the ice, rather than provide a bounce-back reading, making altitude even more difficult to judge and maintain.

Approaching the contractor helicopter crash site, Branch could tell, visually, that the aircraft had sheered its engine mounts, indicating that all power had been lost and, from a high hover, which Branch later estimated to have likely been somewhere around 175-to-200 feet in the air, the helicopter had dropped straight down for a very hard land impact. “The pilot (sole occupant) was trapped in the wreckage, with compound fractures and, needless to say, he was in bad shape, really bad shape,” recalled Branch. Assuming there would be injuries, two McMurdo Sound-based firefighter-paramedics flew along on this rescue mission. And good thing, because four of the five on board, including Co-Pilot Branch (the Aircraft Commander stayed onboard to keep their helicopter running), had to work hard and fast to free the injured pilot. “We had to use crash axes, and whatever else we had available, to try to start pulling the downed aircraft apart just to get him out,” said Branch.

Site of the helicopter crash in Antarctica. Front canopy section forcefully removed by Branch and his supplemented crew, in order to rescue the badly injured pilot. In the background, a barely visible rock cliff, shaded by fog, that Branch had to avoid en-route to the downed helicopter.

And once they were able to do that, he was in for a surprise. Come to find out that the badly injured contractor pilot was retired from the Coast Guard!

“Long story short, we ended up tearing the heck out of that helicopter, we got him out, got him on a backboard, put him in our helicopter, and began the flight back to McMurdo for medical care. We hadn’t realized until then that the injured man was a retired Coast Guard pilot. He’d been passed out from the pain and loss of blood, until he heard the familiar sound of the approaching Coast Guard engines, and as we were loading him into our helicopter, he came to, his eyes briefly darting around, recognized he was in the same type of Coast Guard helicopter he had flown, gave us the thumbs up, and passed out again!,” Branch clearly remembered.

The McMurdo paramedics onboard worked to stabilize the injured pilot. While the rescue, onboard medical attention, and return flight to McMurdo were all underway, a C-141 “Starlifter” was launched from Christ Church, New Zealand, with medical personnel, including a trauma surgeon, and advanced treatment facilities, effectively a hospital in the sky, which would then transport the injured pilot from Antarctica back to New Zealand for continued, land-based, medical care.

But how and where to safely land an aircraft of that size? Branch explained. “McMurdo Station has the world’s only ice runway. Pegasus Airfield is actually out on the Ross Sea. The ice is about 20-feet thick, so they can actually land and launch cargo jets on it. By the time we landed at McMurdo, beating the C-141 there by just a little bit, we were set to make an immediate aircraft-to-aircraft transfer. Once he was onboard that large jet, he was in very good, experienced hands.” Best news of all for everyone involved in that risky rescue, Branch later learned that the injured pilot did pull through.

Lieutenant-Commander Branch (left seat in view) en-route to a mission (2008).

Following the Antarctica assignment, in 2003, LT Branch was selected to enter the aviation engineer career track, along with his flying duties, and was transferred to Air Station Traverse City (Michigan). He wanted the aviation engineer option, rather than operations officer, because it would mean spending most of his career “on the hangar deck.” This kept him constantly around the helicopters, flight mechanics, and crew. Being around all of those folks for the bulk of his career was exactly where he wanted to be. It was at the Traverse City Air Station that, now-Lieutenant Commander Branch became an Aircraft Commander, Instructor Pilot, and Flight Examiner in the upgraded HH-65B.

Northern Michigan has some really challenging winter weather conditions. Despite that, outdoor activities like snowmobiling, ice fishing, cross-country skiing, hunting and other recreational hobbies are popular, and on occasion, can result in problems, especially with sudden changes in the weather.

One night, while LCDR Branch was on duty, he got a rescue call regarding a hunter who had failed to return home. “He was out on one of the Western Michigan islands (reached by personal boat). It was snowing pretty heavily that night, so we launched out, because they couldn’t get a boat to the island. The storm had blown up so much that there was no way he’d be able to use his own boat, with the approximate 5-to-8-foot seas. Making matters more urgent, with temperatures approaching zero, and gusty winds, they learned that the hunter wasn’t equipped for overnight survival. Fortunately, there was a State of Michigan wildlife officer housed on that particular island. The challenge, now, was getting that officer together with the hunter in the midst of what had become a blinding snow storm.

Thus the pressing need for Branch’s crew to get overhead to try to locate that hunter. “The snow was so heavy, making visibility very limited, and it was at night, so we were flying with night vision goggles. And flying through snow like that almost completely overwhelmed the vision part of the term night vision goggles!,” remembered Branch. Beyond the snow, adding to the difficulty of spotting the guy was the fact that the island was very heavily wooded.

It all came down, luckily, to one habit on that hunter’s part that may well have saved his life. “We finally found him, when we saw him light a cigarette! And on the night vision goggles, that popped pretty clearly on a very dark island. Then, through some radio relays, we were able to direct the wildlife officer over to him, so that he could get him back to the officer’s hut to warm up. We did learn that he was pretty hypothermic. If we hadn’t found him that night, he wouldn’t have made it,” concluded Branch. Ironic, then, that, on this totally dark and freezing night, in a twist to the norm, this was a life actually saved, thanks to smoking!!

Since they had flown all the way out there, in very challenging winter conditions, for their effort, had they considered simply hoisting the hunter up and off the island? The answer to that question was a pretty quick No. “With every rescue situation, you have to make a judgment call. Hoisting is dangerous. People think that just because, in this case, you found him, you need to hoist him. Sometimes, the boat transfer, the shore transfer, or the shore forces taking that person into their care, is better because its less stress on someone already impacted by their situation, or even in shock, so that sometimes flying them out is not the best plan,” said Branch.

Even as an Air Station Commander, that person remains in the rotation to “stand duty.” One night, in January of 2018, while Captain Branch and his crew were on-duty in Charleston (Air Station Savannah rotates a crew every day to staff and cover Air Facility Charleston), a call came in from a fishing vessel that was about 75-miles off of Cape Fear, North Carolina. “It’s the middle of the night, with 10-to-15-foot seas, and probably about 45-mph winds. We were told that the captain had gotten his arm caught in the reel mechanism that helps to bring up the long-lines. He’d mangled it pretty badly and was bleeding heavily. We consulted with the on-duty fight surgeon (available by phone 24/7 to evaluate requests for medical evacuations) and he said, yeah, you need to get this guy off,” said Branch. Because of the distance from shore, and with it, the lack of helicopter-to-base radio reach, joining the rescue team was a C-130 from Elizabeth City, North Carolina, to fly overhead providing radio relay back to the coast. “Having fixed-wing coverage when we’re that far off shore is really important for the safety of my crew. They can also help prep the ‘battlefield’, because one of the rules of SAR (search and rescue), that we grew up learning, is that most of the things you’re told about the case, en route, aren’t true, and, unfortunately, there’s some truth to that old adage!,” said Branch.

And case in point, when they arrived on scene, the vessel was not at all what they were expecting. Based on past such missions, they thought they’d be finding more of a regular commercial fishing boat, with a big open deck in the back, and trawler arms. Instead, they were looking down at a vessel with a covered deck from the very front of the boat all the way to the back. For starters, it was then obvious that there was no way for the boat’s injured captain to get up on top for the rescue. Adding further to the complexity of this particular rescue operation, there was a large PVC-pipe-encased antenna bolted to the side of the pilothouse, reaching up about 40-45-feet in the air, swinging wildly, “like a sailboat mast,” recalled Branch, as waves from the heavy seas pitched that boat back and forth like an out-of-control rocking chair.

With Branch having to keep his aircraft well clear of that tall, whipping antenna, there was no way of safely placing his rescue swimmer on that boat. Throughout all of the on-site observations and rescue what-ifs, running rapidly through his mind, along with continuous input from his crew, the fuel-state of his aircraft remained an ever-pressing reality and concern. And with remaining fuel now soon to become a factor, given their distance from shore, a rescue decision had, and all hoped the right one, with fuel and safety diminishing their options. After first trying to maneuver close enough to pick the captain up off the back of his boat, but prevented by that dangerously whipping antenna, following a quick consultation with his crew, Branch opted to execute a water rescue (i.e., the person(s) to be rescued must actually go into the water), rarely the first choice, especially with a boat that’s rocking wildly, but dictated here by circumstances. Branch communicated the rescue plan by radio to the injured captain. He was OK with whatever method would get him to medical attention the quickest. The fishing boat’s deck-hand then helped his captain get into an on-board water survival suit. Once ready, the captain, no doubt hurting, somehow rolled himself into the water off the stern of his boat. That step completed, Branch maneuvered his hover as close to the rear of that boat as he safely could, then lowered his rescue swimmer down into the water near where the captain was floating, where the swimmer, then, assessed the injured man’s condition, and prepared him for hoisting, as quickly and expertly as he could, under the illuminating beam from his helicopter above, in that pitch black night battling a churning sea.

When the swimmer signaled his crew-mates that all was ready, the rescue basket was lowered from a height of about 30-feet, the preferred distance above the surface for hoisting. The swimmer then helped the boat captain into it, and the basket hoist was then successfully completed. Once safely inside the helicopter, Branch chose to leave the injured mariner in that basket to save time initiating the return flight. The swimmer was then quickly pulled up into the aircraft, by the standard method, with the hoist hook connected securely to his insertion harness. With all now onboard, Branch and crew then headed directly for shore, with, thankfully, enough fuel to make it back to the field at Cape Fear, but very little more. Without the needed fuel to fly directly to a hospital, the overhead C-130 radioed shore to have an ambulance meet the flight at the field, and then transport on to medical attention.

The boat was fine and the deck hand was able to get it back the 75-miles to shore. “We try to work with mariners when we have to pull them off their boats. We realize that if the boat is left without any crew, it’s bound to get destroyed or stolen. Assuming someone(s) is left onboard, we’ll typically have a small Coast Guard boat from shore go out and meet them somewhere. We’ll also have them in radio communication with the Coast Guard Sector, so those on the boat can report in every 30-minutes or so that they’re still OK. And we’ll coordinate with Sea-Tow if it ends up that they need assistance making it to shore,” said Branch.

Branch did find out that the boat captain survived, but uncertain whether doctors were able to save the arm. Getting him off that boat by air was definitely the right call. “He was in bad shape,” he remembered.

On the much lighter side, Captain Branch recalled an unexpected, and most unusual, side activity from back when he was in flight school. Renting a house there with his wife, one day a neighbor happened to mention that the local minor league hockey team was looking for a new person to play the role of mascot. Branch responded that, for a year at the Academy, he had been a team mascot, “so if they’re looking for someone with college experience, have them call me,” he said in an off-hand joking manner, thinking that neighbor was kidding. The very next day, he got a call from the owner of that local hockey team indicating that he’d heard that Branch might be interested in the mascot position! Branch was, at first, convinced this was a prank call from one of his buddies in flight school. So the caller said, let me try this again. He repeated his name, said again that he was the owner of the Pensacola Ice Pilots, and that he needed a yes or no answer. Realizing the call was legitimate, this time Branch replied, yes, he’d like the job. And so, with the permission of his Squadron Commander’s approval (agreeing that this approval would be just between the two of them, so that when fellow commanders went to the hockey games, they wouldn’t know it was Branch in costume), he was hired as the team’s mascot, known as the “Iceman”! His costume consisted of a hockey outfit from the neck down, with a cartoon character head-piece, topped off with the old-school flight cap and goggles. Clearly not the ideal look to impress a date (or anyone else, for that matter). Branch’s “Iceman” appeared in two to three games per week for about six-months. Remembering all the while that his demanding daytime pursuit was training to earn the wings of a Coast Guard pilot.

The Navy’s Blue Angels are home-based in Pensacola and would often do out-on-the-ice promotions for the “Ice Pilots,” who drew their name from this world-renown flying team. Before one game, Branch was on the ice sitting next to a Blue Angel pilot. After a brief greeting exchange, the pilot leaned over to Branch and said that he’d been told that the “Iceman” was actually a flight student, and asked if that was true. “Yes, sir, it is,” said Branch, notably surprised by the sudden question. “Wow, that’s awesome,” replied the Angels pilot. Sensing a unique opportunity, Branch quickly thought to himself “if I don’t ask, I will hate myself for the rest of my life.” Not wanting to lose the moment, he leaned back toward the pilot and said: “Well, sir, if you ever need ballast in the back of Number 7, let me know, I’m happy to do it!” Without hesitation, the pilot leaned back toward Branch and said: “What are you doing tomorrow?” Branch was stunned by what he’d just heard. He responded: “Sir, please don’t mess with me, because I will drop dead right now if you’re messing with me.” The pilot let him know he was quite serious and to be at the hangar the next day at “zero-8.”

Coast Guard Flight School Student Lieutenant Marshall Branch flying in a Navy F-18 with the Blue Angels! (1998).

“So I was at the hangar at zero-7!” said Branch. He had phoned, in his words, “people I hadn’t talked to since pre-school.” Exaggeration, of course, but a clear indication of how very special he knew this opportunity would be for a student pilot, or anyone else for that matter. And his opportunity of a lifetime Blue Angels flight was “awesome.” “They were doing an air show practice that day, and the lead solo swapped out his Number 5 jet for Number 7 which is the two-seater. Sitting in the back seat of Number 7, they did the full practice, so we were the opposing solos that do the criss-crosses, the high angle of attack, and all of that.” The next few minutes were to even more significantly elevate this elite exhibition flight dream come true. About half way through the practice, the Blue Angels pilot asked Branch how far along he was in flight school. Branch responded: “Just finished aerobatics, sir.” To which his pilot said: “Outstanding…your controls!” At that totally unexpected instant, in the midst of this demanding and precise exhibition flight, Branch could only say to himself: “do what?” Just then, the opposing jet, next to them in the pattern, throws the nose down and takes off. “Well you’re never going to catch him unless you do something!” exclaimed the pilot to Branch. “So I pushed the nose forward, and pushed the throttle up, and immediately I could feel my face distorting. I just never knew you could feel G-forces that way,” he remembered.

After more time than he ever could’ve imagined piloting that elite jet through loops and barrel rolls, his Blue Angels flight host once again took the controls for the duration of the flight. But what an unexpected, fantastic experience for a Pensacola flight student, who of all things was doubling as a hockey team mascot, and just happened to be at the right place, right time, with the nerve to ask the question. “So I got to fly a whole practice program with the Blue Angels, and the Navy yeoman even put in my log book. So now it’s permanently in my flight log book that I have 1-point-3 F-18 time, and point-8 of that is First Pilot, which means I was at the controls! I am one of the only, if not the only, Coast Guard pilot with actual F-18 flight time,” said Branch, describing that memory now, and after all these subsequent years of demanding and courageous Coast Guard flight, yet still, understandably, more than a little awed by that unique experience.

Jumping ahead several years, after giving up his brief brush with show-biz (the “Iceman”) and, more importantly, earning his wings, along with the ever present water-craft rescues, no matter the Air Station assignment, and the narcotics interdiction role handled at some, Branch and his respective flight teams have been called upon to handle some highly important Presidential air-escort missions as well, generally conducted with little or no advance public awareness, and purposefully so. For Branch, this mission occurred primarily while he was assigned to Air Stations in Traverse City, Michigan and Los Angeles., working closely with the Secret Service, whenever the President was on the move.

“We do the security zone enforcement, and we also do the “huntsman” mission, which is where we are the airborne platform for the Secret Service agent watching over the motorcade. In that role, we do the site survey right before Air Force One lands. Once the air space is cleared out for Air Force One coming in, the Coast Guard helicopter will do a lap around the airfield, checking the perimeter with the Secret Service agent in the back, just double-checking to make sure everything’s clear. As Air Force One’s coming in for a landing, we are the only aircraft anywhere close by. So I have been able to get ‘on’ Air Force One’s wing as its coming in, and ride that in. Once on the ground, the President jumps right into his motorcade. When the motorcade pulls out, we lead it in the helicopter, flying about a mile ahead. The agent in our helicopter has the radio and he’s calling down about any cars stalled on the side of the road or anything else that looks to be a hazard and wasn’t pre-briefed. The Coast Guard becomes the visible airborne asset, although there are other assets in the air that aren’t quite as visible,” related Branch

And speaking of motorcades, while serving in Traverse City, Branch recalled flying with a 2004 Presidential one all across the Mid-West. As he remembered it, President Bush would stop at every town hall along the way. He would hold a big rally at each stop, then rejoin the motorcade, and head down the road again. Branch would land in a field next to where these town halls were being held and wait for President Bush to come out. “When word came that he was ready to go, we’d pull up in the air and lead the motorcade again,” remembered Branch. This pattern repeated itself for several hours.

But on this particular day, the weather was starting to get bad. As it got worse, and the clouds grew lower and darker, they soon heard over their radio ‘Aircraft Disengage,’ that order given due to the increasingly poor flying weather. “At that point, then, there were only two of us left with the motorcade, our helicopter and Marine One, the helicopter that supports the President. As I recall, the motorcade was just pulling into Iowa. We were now following the Presidential vehicles flying just above the road. We’d slowed back to about 50-knots, so that we could see and avoid powerlines and things like that,” said Branch. But despite the weather, his helicopter and the Marine aircraft stayed with the President’s motorcade the whole time. However, with one unexpected operational change. Since the Marine helicopter didn’t yet have the Coast Guard helicopter’s advanced avionics, providing a welcome assist for bad weather flying. For safety, Marine One then began flying behind Branch’s aircraft. Major credit to the Coast Guard!

Branch: “When we finally approached the airport (overnight stay location), we called up to the tower to let them know we were arriving. The tower responded: ‘Well you’ll just have to tell us when you land, because I can’t even see the runway from the tower!’ So we climbed back up over the airport and all we could see were the end of the runway lights. We had to very progressively come in, and then we landed. The tower next said: ‘You’ll have to tell me when you’re on the ground, because I still can’t see you.’” Branch told the surprised tower controller that they had landed and were safely down. Then they shut down the aircraft and ‘buttoned it up’ for their Iowa stay that night. Soon a gentleman approached Branch and his crew, introducing himself as a Secret Service agent with the security detail for the President’s motorcade. He then said to Branch: “Hey, nice job to you and your crew. You guys were the only air asset left. We kept looking up through the window of the limo wondering how in the hell are those guys still flying!!” Quite a compliment to Branch and his crew from a federal agent who, one can assume, in his line of high-stress work, was not normally or easily impressed.

A nice compliment, certainly, but given following Coast Guard flight in far less than ideal conditions. Conditions that were, in fact, risky for Branch and his crew. Regarding the risk element that to varying degrees is almost always present, from the limited degree when shadowing a VIP motorcade on a clear day, to the extremes experienced with a nighttime rescue at sea in stormy weather. “We’re (Coast Guard flight crews) Type-A personalities,” responded Branch on the subject of flight risk. “When we get launched, we expect to complete the mission. But there are times when the level of the emergency doesn’t warrant that level of risk. For instance, if flight conditions pose an extreme challenge, and the person(s) needing rescue is definitely not in a life-threatening situation, the risk-based decision may well be to either wait for the weather to clear or, if available, let a Coast Guard boat make the rescue,” said Branch.

“We have lost aircrews,” he continued. “We went through a period about twenty-years ago where we lost about six aircraft. It impacted us all, deeply. We’re a small service, and aviation in the Coast Guard is even smaller, so we knew people who were on every one of those aircraft. It was a pretty dark time for Coast Guard aviation. I lost friends and mentors,” remembered Branch.

As a result of those significant losses, policies were changed. “There’s an old adage in the Coast Guard that says: ‘You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.’ It was after that time-period of dramatic loss when we officially got away from that. You have to come back, and as the aircraft commander, your job is to bring your crew back. So sometimes you have to make the call, where the safety of your crew is balanced against what it is you’re trying to accomplish. And I think as a service, we’ve come a long way in formalizing that risk-management process,” said Branch.

As an example of that change in risk-management policy and practice instituted after those significant losses from several years back, Captain Branch cited an example. “One of the rescue flights I lost a friend on was a case off of Humboldt Bay, California. A sailing vessel was getting torn up pretty badly. Terrible storm out there. Those on board were scared and injured. But in the end, we lost a helicopter in that storm. That crew did not come home. The sad irony is that boat made it back to shore under its own power!” From that experience, said Branch, “we learned a lot about us pushing the issue, because we want the rescue. Now with risk-management, evaluating the situation, not only before you leave, but as you get on-scene, and more facts become available, we continue to assess our risk.”

“One of the things I’m the most proud of with Coast Guard aviation,” continued Branch, “is that we have a concept called CRM: Crew Resource Management. The whole purpose of that concept is, if we hit the water, we’re all going to go down together. So every crew member has a stake in this game. Everybody’s voice matters. And we train every member of our crew to speak up. Talk about risk, talk about concerns, talk about changes to the game-plan. Before the flight, and absolutely during it. We’ll actually evaluate people on their ability to speak up. That’s now become a part of who we are.

Co-pilots, we expect them to speak up and take the controls if the aircraft commander is incapacitated or doing something he or she shouldn’t be doing. We expect the flight mechanics to speak up, and say for example, hey, you’re below the altitude you briefed. We expect the rescue swimmers to speak up and say, for example, hey, did you guys see this aircraft behind us to our right? Bottom line, we expect everyone to speak up, because we all have a stake in the safety of our flight.”

And, if there’s any person in that aircraft, said Branch, no matter how new they are, and no matter how senior the aircraft commander is, if they don’t speak up, then they consider this important, potentially life-saving, crew safety measure to have failed. “So we really harp on CRM (Crew Resource Management) in a big way in the Coast Guard, because we’ve lost crews, when someone should have spoken up, and didn’t. Thankfully, today, I feel that we’re in a much better place. Our risk-management processes, and our CRM, have kept a lot of crews safe. Because we do fly into bad stuff. Unfortunately, we don’t get most of our calls on beautiful days!,” said Branch.

On June 22, 2018, Captain Branch’s two-year assignment as the Commander of Coast Guard Air Station Savannah, ending all too quickly, drew to a close. His one remaining duty was the traditional Change of Command ceremony, which was held in the Air Station’s hanger. At that time, Captain Branch relinquished command to Commander Brian Erickson, who transitioned to Savannah from a tour at Coast Guard Headquarters in Washington, D.C. Presiding at the ceremony was Rear Admiral Peter J. Brown, Commander of the Seventh Coast Guard District, headquartered in Miami, Florida. Among the many attendees, fellow Coast Guardsmen and friends, old and new, was Army Major-General Lee Quintas, Commanding General of the Third Infantry Division, Fort Stewart and Hunter Army Airfield, who recently returned from a nine-month deployment to Afghanistan. Also in the audience that day was Army Lieutenant-Colonel Ken Dwyer, Garrison Commander at Hunter. Coast Guard Air Station Savannah is a tenant unit on the Hunter installation, which is proudly home to personnel from all five military service branches.

Captain Branch leaves the Air Station for a two-year assignment as the Coast Guard’s Liaison Officer to the Navy’s Fleet Forces Command in Norfolk, Virginia. “I’ll be the lone Coastie, on a very big Navy base, working for the Four-Star coordinating operations, exercises, and mutual support,” said Branch. “The Coast Guard actually uses the Navy quite a bit, both in law enforcement and, at sea, for the war on drugs. Their sensor capabilities are excellent. We will put specialized boarding teams onto destroyers and frigates, and once they detect something that needs to be intercepted, they will hoist a Coast Guard flag over the ship, shift authority to us, and their ship becomes, in effect, a Coast Guard Cutter, now with law enforcement capability. For search and rescue, major surge operations, like hurricane response, we’ll use the flight-deck equipped Navy ships as ‘lily pads’ for fuel and logistics support (for CG helicopters). We’ll also bring in the Navy’s amphibian ships for command and control for major operations like Hurricane Irma in the Caribbean,” he said.

Branch was asked what had been his most satisfying assignment in the Coast Guard. “This one (Air Station Savannah), no question” he responded without hesitation. “As a pilot, you want to go fly the missions. You want to do the rescues. You want to do all that stuff. It’s just in your blood. But watching these crews here go through two historic hurricane seasons. Surging to Texas, to Louisiana, Florida, Puerto Rico. Flying into the teeth of those storms and saving dozens, upon dozens, of lives, each. I’ve got a first-tour guy who has more lives saved than I had in my whole career. Because he was down at Hurricane Harvey and the whole time he was there, he was just pulling people off of houses,” remembered Branch.

“And I’ll tell you, there’s a part of you that wants desperately to go. You want to grab that helicopter and go. But there’s something so supremely satisfying about watching your crews go out there and make it happen. The pride you have in them getting the job done. And that’s what I’ve waited this long in my career for. And it’s happened here. It’s more than I could ever have expected. It’s been amazing, said Branch.

Deployment to Kuwait to support Coast Guard Port Security Unit 309, conducting Harbor/Port Security Missions at Kuwaiti Naval Base/Camp Patriot.

If it happens that there’ll be no more flying with your next assignments in the Coast Guard, what will you miss the most? “The people,” replied Branch, again with no hesitation. “The reason why I went with the HH-65B helicopter is because it’s the one that deploys on the backs of ships. I wanted to deploy with the crews. When you deploy with a unit, you create a much stronger bond than when you’re in garrison. And I wanted to have those experiences where I deployed with the crew and really got to know them. We worked together to accomplish missions, to achieve tangible results, and that’s something that will forever be with me. The crews that I deployed with (Eastern Pacific, South America, Antarctica), are the crews that I keep in touch with the most.

The Branch Family arrived for a visit with Dad at work, just as a SAR case call came in! So the kids got to watch while Dad and his crew “spool-up” the helicopter prior to launching on that mission.

And I guess that’s why this command tour has meant so much to me. I feel like it’s been a two-year deployment with a hundred people! I’ve gotten to know each and every one of them and their families. I’ve been able to celebrate the good times, and I’ve been able to help them through the tough times. And I think that’s what’s made it really special,” said Branch.

Looking ahead, there’s something else that’s really special, really important to him. “I’m still loving my job with the Coast Guard. I smile on the way to work. And as long as that keeps happening, I’m going to keep doing this until they tell me to stop!” concluded Captain Marshall Branch, with the same genuine enthusiasm, commitment, and caring that he’s exhibited throughout his Coast Guard career.

PERSPECTIVES ON LEADERSHIP: USCG Captain J. Marshall Branch

What do you feel are the most important elements of a leader’s character?

For me, I’ve always subscribed to the three “C’s”: Compassion, Candor, and Commitment. You cannot lead if you do not have compassion in your heart for those you are responsible for. Compassion allows you to put your people first, care for their needs and growth, and temper corrective actions with a sincere desire to learn what factors were behind any missteps. Candor, or honesty, is absolutely critical. Your people are smart. They will see through a façade. Be candid about your own shortcomings and mistakes, as well as those in your charge. It is important to temper candor with compassion, the combination of the two allows your team to know exactly how they are performing, while remaining confident that you have their backs and are supporting them to succeed.

Lastly, you cannot expect anyone to be committed to a cause when they don’t see that same level of commitment in you. Commitment is more than words. It is the actions you take to show the priority you personally place on the missions your unit is responsible for. If you say “safety” is a priority, you better live that mantra. If you say proficiency is important, then you better be getting as many reps and sets as you can. Again, military personnel are smart, and they pick up on hypocrisy, real or perceived, and that can undermine success. Commitment is the root of the phrase “Lead from the Front.”

Please provide a memorable example that you’ve observed of exceptional character in leadership.

In the context of leadership, my most memorable observation comes from Hurricane Katrina. Then- Commander Bruce Jones (who retired as a CG CAPT) was the CO of Air Station New Orleans during the Hurricane Katrina response. As you can imagine, nearly every member of the crew of Air Station New Orleans suffered extensive damage to their homes and possessions. The Air Station was torn to pieces, all power lost.

Despite it all, CDR Jones kept his crew motivated on the task at hand. His Air Station was the first to launch aircraft to rescue those trapped by the flood waters. And they continued to do so for the next 2 weeks straight. Around the clock operations, sleeping on hangar floors and in un-air conditioned offices. CDR Jones checked on every member of his crew, and every transient crew that descended onto Air Station New Orleans (over 30 aircraft clogged the ramp of his 5-helicopter unit running SAR operations 24/7). I arrived 4 days into the operation as the senior member of the Critical Incident Stress Management Team, a team of aviation peers trained to help prevent PTSD in operators. I watched as CDR Jones inspired his exhausted crew, pulled every string he could to get FEMA trailers brought to the Air Station, so the crews could get adequate rest, and even managed to get a portable shower trailer brought on base.

It was into the second week of the response that I was trying to find CDR Jones, to brief him on some crew issues, and I couldn’t find the CO’s FEMA Trailer. None of the crew knew which one was his, so I went to his office to try to find him (which was in the command building that had flooded and, to make matters even worse, had an inside temperature well over 100 degrees). As I knocked on the door, I heard some rummaging and a quick “Come in”. As I opened the door, I saw CDR Jones quickly pushing a bedroll under his desk. I said, “Sir, do you not have a trailer to sleep in?” He looked at me and shared that he would not sleep in one of the air-conditioned FEMA trailers, until every member of his crew was able to, as well (the trailers were trickling in about 4-5 per day at the time). That’s when it hit me. “Sir, your crew doesn’t know you are sleeping in here, do they?”. He didn’t answer, but he did ask what it was that I had come to tell him about his team. CDR Jones put his crew first, because he genuinely cared about them. But he didn’t do it to fanfare. And he didn’t even want them to know about it. Because he didn’t want them to have the distraction of being concerned about their CO sleeping in hot, moldy office.

CDR Jones led the most tired crew I’ve ever seen, through the most historic rescue operation in our 200-year service history, saving over 12,000 lives and without suffering a single mishap. More importantly, every member of that Air Station New Orleans crew would have stormed the gates of Hell for CDR Jones. That’s why CAPT Bruce Jones was the first person I called, when I was told that I would be commanding Air Station Savannah. Because he’s the kind of leader I strive to be like.

What do you feel are the most important traits or qualities of exceptional leadership?

I feel like this dovetails with the question about character. The two are inseparable. You can’t be an effective leader without character, and the qualities that define character also define effective leadership. Aside from the character qualities, you could add traits such as communication and vision. A leader must have a vision for where the unit needs to go in terms of mission, professional growth, and performance. In concert with that vision, the leader must be able to communicate what is desired in a way that the crew can digest and adopt. Additionally, communication requires the ability to listen. A good leader knows how to listen to trusted advisers, to contrarians, and to the masses. Listening to trusted advisers enables you to gain critical insights for improving the effectiveness of your plan. Listening to contrarians forces you to think about perspectives other than your own. And, finally, listening to the masses allows insight into how your message is being perceived at various levels.

Please provide a memorable example you’ve observed of exceptional leadership.

CDR Jones’ example above is, without question, the finest example of leadership I have personally observed. That said, another example that struck me early in my career was that of a previous Commandant, ADM James Loy. Early in his tenure as Commandant of the Coast Guard, a particularly nasty public affairs crisis had developed. Just off the beach in Miami, a Coast Guard small boat had intercepted a tiny vessel with Cuban migrants attempting to make it to shore. At that time, the “Wet-Foot, Dry-Foot” policy required Coast Guard teams to try everything possible to prevent migrants from making landfall. In this situation, several migrants had jumped into the water in an attempt to swim to shore. As a news helicopter flew overhead, and as news teams on the beach recorded, the Coast Guard crews escalated through our Use of Force rules (our ROE) and ended up spraying the migrants in the water with pepper spray, in order to stop them from swimming further, so they could pull them onto the Coast Guard boat. The public outcry as this played live across the country was deafening.

As a young Junior Officer, I fully expected the Commandant to either avoid the cameras by sending out a spokesperson, or to simply blame the boat crew for being too overzealous in their interdiction. Instead, ADM Loy went in front of the cameras and stated that they were following current Coast Guard policy, “My policy”, and that he realized, due to this incident, that the policy is flawed. Repeatedly, he told the interviewers that he ‘owned’ the policy that caused this event, that the boat crews had effectively followed his policy, and that, going forward, he would change it. I was stunned. And impressed. The ADM protected that crew the right way, put the fire of public outcry squarely on himself, and fixed the problem!

How do you define courage? Is there a memorable example of exceptional courage?

I define courage as being scared, but doing what has to be done. I define exceptional courage as being scared s—less, but doing what has to be done in a way that reassures those around you that the response you’ve chosen is going to work out. I’ve been blessed to see that done regularly in my job. Coast Guard aviators consistently go out in the worst weather, over the nastiest seas, to save people in exceptionally bad situations. Pilots, aircrew, and rescue swimmers exhibit bravery and courage so routinely, that it actually almost becomes routine.

If pressed for an answer, I would point to an Air Station Savannah Rescue Swimmer named Garrett Downey. The aircrew was launched to respond to an emergency beacon 40-miles off Charleston. They happened to have a Go-Pro and filmed the entire rescue (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KxIiN559Jms). At around minute-6, you can see Garrett swimming fast up to the overturned boat, pulling himself aboard, and talking calmly with the survivors of the now exceptionally distressed vessel.

What you don’t know, is that as soon as he entered the water, a large Mako shark started chasing him and made several aggressive runs at him, trying to bite him. Garrett swam fast, punched back, and continued to the vessel to rescue those boaters. Once on the overturned vessel, you would never know he was being chased by a shark. Later, the survivors would enter the water to be picked up by another boat that had pulled alongside. Garrett stayed in between the shark and the survivors to make sure they all got on the rescue boat safely. That’s being scared s—less, but regardless, doing what has to be done, while keeping those around you calm while doing it!

What have you most valued about your military career? What has your military experience meant, and, importantly, given back to you?

First and foremost, I value the continuing career service to this country that I love. I consider myself incredibly blessed to have been in a position to help those who needed to be rescue, and to have contributed to the defense of our nation during my time in uniform. It has been an honor and a privilege to be able to perform the myriad types of missions the Coast Guard achieves every day, from rescuing those in peril, to interdicting illegal drugs, to protecting our environment, to enforcing homeland security, and supporting homeland defense. Every single day of my 20+ year Coast Guard career-to-date, I was able to directly serve my country and my fellow citizens. That has brought me incredible pride and purpose.

A very close second is the brotherhood/sisterhood of military service. I’ve been blessed to serve with some of the finest men and women that I have ever encountered. The friendships you develop during a military career are every bit as close as family. Military service has given me mentors, friends, and experiences, that have both made me a better person, and enriched my life. I’ve grown as a person through the challenges of leadership and responsibility, with sincere thanks to the tireless efforts of some very talented Chief Petty Officers, senior officers, and junior enlisted. I’ve seen the best our nation has to offer. And I continue to be inspired by the endless number of truly great Americans, talented, dedicated people, of all ages, races, and backgrounds.

(Copyright 2018, William L. Cathcart, Ph.D.)